Rec. Dates : November 12, 1956, November 13, 1956

Stream this Album

Piano : Hampton Hawes

Bass: Red Mitchell

Drums : Bruz Freeman

Guitar : Jim Hall

Cashbox : 06/14/1958

The common denominators here are: (1) the quartet membership is the same on all three disks; (2) the sixteen selections on the separately issued packages were recorded in a single, two hour session and; (3) accomplished pianist Hawes, backed by four pros, sets a continually inventive, mostly buoyant jazz pace. The three other jazzmen: Red Mitchell (bass); Bruz Freeman (drums) and Jim Hall (guitar). Three platters reflecting a great swing-bop upbringing.

—–

American Record Guide

Martin Williams : September, 1958

Hawes had been playing a capable but basically conventional modern jazz piano on the West Coast until, in the late fifties, a series for this label (C3505 and especially C3515) showed a man apparently finding his voice in part in an exciting elaboration of the “funky” blues-and-gospel-based style of Horace Silver. On this series, he somehow makes almost unassimilated references to almost every pianist of the last fifteen years, but plays most of the time in the highly rhythmic but eclectic and fragmentary manner of Oscar Peterson. A reviewer’s advice to a company is gratuitous, but to preserve all of this on three records is to give unevenness a strong sanction.

—–

Harper’s Magazine

Eric Larrabee : November, 1958

Hampton Hawes is a West Coast pianist with a modernist’s subtlety and crispness. Contemporary Records sent me three albums of his with a note, commenting on the difficulties Alan Lomax had getting Jelly Roll Morton down on wax and the ease with which something similar can now be done. The three Hawes records are all from a single session. The company argues that for a sustained performance this is extraordinary, and that as a representation of “live” music it is uniquely authentic.

They have a point. Hawes is also an exceptional pianist in that he can make sounds like background music but can also invest them with substance. These are records that you can put on for the packaged atmosphere of a relaxed evening, but if – by any chance – you should want to listen to them, there is something there to hear.

—–

HiFi Stereo Review

Ralph J. Gleason : September, 1958

This is a most remarkable collection of sixteen tracks of improvised jazz, recorded at one all-night session by pianist Hawes, guitarist Jim Hall, bassist Red Mitchell and drummer Bruz Freeman.

Hawes has had the same sort of influence on jazz pianists on the Pacific Coast as Horace Silver has had on eastern musicians. Such pianists as André Previn have been directly and deeply influenced by his work.

On this LP, he is lucky to have the framework of a group that fits together instinctively, as though they had spent a lifetime sharing the same bandstand and experimenting on the same chord changes. In Jim Hall, Hawes has one of the few new guitarists able to combine good rhythm section work with a strong lyric line (he was once featured with Chico Hamilton) and in Mitchell, he has one of the most lyrical of all bassists. Drummer Freeman is able to produce that most difficult of percussion effects – a good, swinging pulse which is felt rather than heard.

Hawes himself, when he is playing well – as he is on these LPs – displays a full-fisted style that at all times insists on a rolling, flowing rhythm. This is why the LPs can be heard advantageously on several levels. The flowing rhythm makes them acceptable as background music; the harmonic ideas and inventive variations of melodic line make them fascinating to the serious jazz listener as well.

Almost everything that Hawes plays is infused with the blues mood, feeling and sound. The discontinuity of phrase in his improvisations is reminiscent of the best of the modern jazz horn soloists and the richness of his harmonic texture, while at times influenced by Garner (especially on ballads), gives his playing a fullness that is lacking in many young jazz piano soloists today.

The numbers range from a short (two minutes, 50 second) version of Two Bass Hit to a long (11 minute, 14 seconds) improvised blues, Hampton’s Pulpit. There are six ballads, six jazz standards and four original blues by Hawes. The latter are, for me, the most rewarding of all, since they clearly express his full grasp of the blues language and ability to replenish it with the knowledge of the literature of modern jazz. There is an excellent essay on jazz piano by Arnold Shaw, which serves as liner notation for the three LPs.

—–

Oakland Tribune

Russ Wilson : 06/15/1958

Pianist Hawes, guitarist Jim Hall, bassist Red Mitchell, and drummer Bruz Freeman settled down in Contemporary’s Los Angeles studio the night of Nov. 12, 1956, and started playing. Sometime the following morning, which incidentally was the leader’s 28th birthday, they ended the session. The result was two hours of modern jazz distributed among 16 tunes, four of them uptempo blues composed by Hawes at the session, now released on three LPs. Hawes has said that the greatest influence on his playing has not been other pianists but rather the late alto saxophonist Charlie Parker. The albums bear this out, not only in Hawes’ conception of time but also in his choice of tunes, among which are five bop standards in addition to the leader’s blues. Hawes, a superb pianist in the Bud Powell axis (as annotator Arnold Shaw points out in his excellent notes for Volume 2) demonstrates flow of ideas, a firm touch, tart harmonies, shifting rhythmic patterns, and pulsating energy. There are good solos by Hall and Mitchell, fine two and three part voicings, and consistent support from Freeman.

—–

San Bernardino County Sun

Jim Angelo : 05/24/1958

Devotees of the modern jazz piano will relish Contemporary’s noteworthy contribution: All Night Session, three definitive LPs by the Hampton Hawes Quartet. These unusual waxings – recorded during a single, continuous session – were pressed without editing of any kind (which, in itself, is extraordinary.) Likewise extraordinary is the keyboard displayed by Hawes, whose improvising throughout shows vitality and spontaneity in the finest jazz sense. Outstanding are his inventive chord patterns on April in Paris (Vol. 2), his penetrating original Hampton’s Pulpit (Vol. 1), and his vivid interpretation of Do Nothin’ Till You Hear From Me (Vol. 3). Invigorating, cohesive support is provided by guitarist Jim Hall, bassist Red Mitchell, and drummer Bruz Freeman. All three disks of crisp, fresh modern music are recommended without qualification.

—–

San Francisco Chronicle

Ralph J. Gleason : 05/18/1958

Hawes at the Piano Carries on the Jazz Message

The piano has always had a very special place in jazz. The great line of piano players stretching back through Tatum, Hines, Waller and Morton were all influential in a much larger field than just their instrument.

Perhaps one of the reasons is that the piano expresses a very broad emotional message in jazz. The jazz pianist paints from a large palette with an infinite variety of colors and patterns to choose from.

In recent years, the jazz piano has been dominated by the erratic Bud Powell who combined blistering technique and a bizarre harmonic sense with a concept of melodic lines on the piano which was basically that of a pair of horns.

Oscar Peterson and Erroll Garner have brought back to jazz the full, orchestral concept but, unlike the arrival of a young pianist named Hampton Hawes a few years ago, there was no member of the younger music generation to carry along their idea.

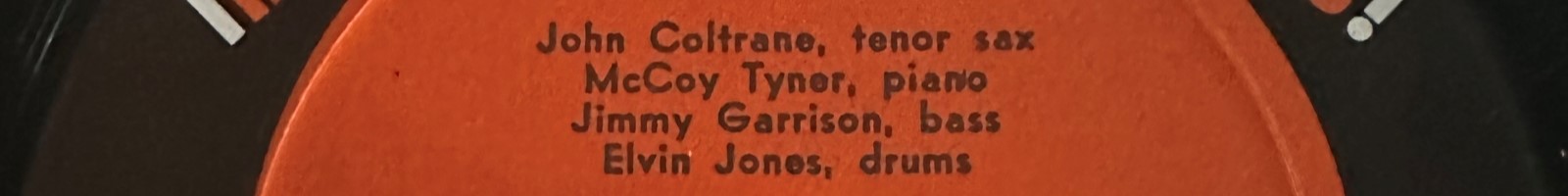

Contemporary has just released a remarkable three volume set of Hampton Hawes. It is called All Night Session and it is, unedited, the result of a single recording session at which the pianist was accompanied by Jim Hall, guitar; Red Mitchell, bass and Bruz Freeman, drums.

Hawes combines the linear conception of Charlie Parker, in which the melodic line runes the gamut of harmonic possibilities and expands the ordinary conception of rhythm, with the full sound and great pulsating drive of Peterson and Garner. He is a most unusual pianist since he combines in his playing many elements, usually diverse. There is the earthy blues feeling, the sometimes almost boogie woogie eight-to-the-bar, the lush, almost Duchin, ballad style, and a fine, solidly swinging beat.

There are 16 numbers in the three LPs. They range from ballads to blues and jazz standards. And aside from the powerful and compelling voice of Hawes there are a number of really moving soloists by guitarist Hall and bassist Red Mitchell who is almost alone among jazz bass players for his effective presentation of a ballad solo.

This is not the sort of album set one can digest in even several hearings; it is valuable jazz music on several levels. One can listen for the various members individually, for the group, for the all encompassing beat and even for the pleasant background. But above all, it is valuable as a documentary of two hours of solid playing by a young man who, if fate is kind, seems destined to become one of the great piano players in jazz.

—–

San Francisco Examiner

C. H. Garrigues : 06/08/1958

Of all the great jazz pianists of the present day, the man who is closest to the musical feeling of the great bop hornmen of the early 40s is probably Hampton Hawes, the young Los Angeles pianist who opened last Tuesday night with the Curtis Counce group at the Blackhawk.

As though to confirm this fact, Contemporary Records last week released a set of three Hawes records which, considered as a whole, constitutes one of the most remarkable jazz achievements since the invention of the LP. Entitled All Night Session, it is the direct record of more than two hours of blowing at a studio date, without interruptions, playbacks, retakes or editing – producing a master which is a complete gas from start to finish: one which includes not only a dozen standards, but four Hawes originals improvised on the spot and only charted later.

If this were a mere blowing session, it would not be too remarkable. But the musicians recognized it as a formal recording date: one which must produce a product with continuity and variety and musical inspiration from start to finish. To say that there was no repetition and no goofs would be hyperbole – but there are astonishingly few of either and after you’ve listened to an hour and fifty minutes you’ll find that the inspiration of the last number flows as freely as that of the first.

True, a great deal of the credit goes to the sidemen. Jim Hall‘s very funky guitar, answering and completing Hawes’ sparkling melodic lines again mark him as the top among jazz guitarists. And Red Mitchell‘s fine bass, stronger than you usually hear it, gives a firm, extended spatial quality to every arrangement. The drummer, Bruz Freeman, is adequate and seldom obtrusive.

But in the last analysis, the credit belongs to Hawes. When you first hear him you are troubled because he reminds you of Monk – though he sounds very little like Monk, in fact. Then you realized you are thinking of Monk because, pianistically, Hawes is feeling and thinking like the hornmen Monk used to play with: Diz and Bird. His ideas sparkle with cascades of fine bop figures as Diz’s did (and do) and as Bird’s did – though, I think, his pressure is inventive and melodic rather than, as Bird’s often was, frenetic and rather desperate.

—–

Down Beat : 08/21/1958

John A. Tynan : 5 stars

Here, at least, is the definitive Hamp Hawes. Spread out over three 12 inch LPs, as is this collection, there is ample opportunity fully to assess the sometimes disputed prowess of the 29-year-old west coast pianist.

As the album title indicates, these sides were corded in one all night record date on November 12, 1956. The four musicians began recording and, as the groove wore smoother, just kept right on going.

All four were in optimum playing spirit. Hawes has never sounded so good on record and now emerges as one of the foremost jazz piano talents of our generation. His roots undeniably lie anchored in the blues and he seldom strays very far from that influence. As a modern blues pianist he remains superb. His ballad interpretations (I Should Care is a good example) tend still to show a little too much extraneous embellishment.

Hall‘s playing throughout is sheer, funky joy. Both as soloist and comper he fully rounds out the group, adding necessary variety of feeling and color to the trio context in which Hawes previously chose to express himself. As for Mitchell, he always is a paragon of jazz bass playing. Freeman‘s drums swing unrestrainedly all the way.

—–

Liner Notes by Arnold Shaw

Volume One

As a group, the three albums and sixteen selections comprising All Night Session! represent a most unusual achievement in the annals of jazz recording. The almost two hours of music were recorded at a single, continuous session, in the order in which you hear the numbers, and without editing of any kind. This seems like an impossible feat. Playing steadily for several hours is a taxing physical experience at best, but improvising continually for that length of time is an exhausting one, mentally and emotionally. Yet the later selections in All Night Session! reveal no flagging of vitality, spontaneity, or inventiveness. “The feeling wasn’t like recording,” Hampton Hawes has said in commenting on the session. “We felt like we went somewhere to play for our own pleasure. After we got started, I didn’t even think I was making records. In fact, we didn’t even listen to playbacks. We didn’t tighten up as musicians often do in recording studios – we just played because we love to play.” Considering the buoyant beat, skillful pacing, variety of material, spontaneous jazz feeling and the richness of invention, All Night Session! is a testimonial of the highest order to the musicianship of jazzman Hawes and his associates.

As a pianist, Hawes possesses a remarkably robust and vigorous style. The sixteen selections in All Night Session! teem with a pulsating energy and are marked by a seemingly inexhaustible stream of ideas. Although he can create chord patterns of great beauty as in I’ll Remember April and April in Paris, and he can command a singing, lyrical tone, he is more attracted at this stage of his career to expressions of a dynamic character. His touch is firm and authoritative and he possesses a split second sense of timing. His technical mastery is so great that there is not a single blurred run, tangled triplet or ragged arpeggio, no matter how fast the tempo.

Included among the sixteen selections are four original compositions by Hawes. They are of interest for two reasons. In the first instance, it is to be noted that they were composed at the record date itself and not written down beforehand. This gives them a spontaneous, ebullient quality, which is in a sense, their strongest characteristic. I was interested to learn that virtually all or Hawes’ originals have been composed in this way. Instead of being written down, they are transcribed from his live performance, emphasizing the fact that his creative activity is the result of his role of an improviser. The second fact to be noted is that all four selections are blues — fast, vigorous blues, but blues nonetheless. Like Charlie Parker, whom Hampton credits with being the strongest influence on his playing, Hawes believes that blues are the basic foundation of jazz and that all jazzmen, modern as well as traditional, must begin by mastering the blues.

Born in the center of west coast jazz on November 15, 1928, Hampton Hawes became a member of the musicians’ union when he was sixteen. The following year, while he still attended L. A.’s Polytechnic High School, from which he was graduated in 1946, he played with Big Jay McNeely‘s band. Before he was drafted into the army in 1953 for the usual two year stint, he gigged around L. A. with various modern combos, among them, Wardell Gray‘s, Red Norvo‘s, Dexter Gordon‘s, Teddy Edwards‘, and Howard Rumsey‘s All-Stars at the Hermosa Beach Lighthouse. The latter assignment came through a meeting with trumpeter Shorty Rogers, who after hearing him at a Gene Norman concert, immediately invited him to play the recording date which produced the first Giants album on Capitol (1952).

On his release from the army in 1955, Hawes took his own trio into L A.’s [The] Haig [on Wilshire Blvd. in Hollywood, CA]. He also recorded his first trio album for Contemporary Records (C3505), employing Chuck Thompson on drums and Red Mitchell on bass. This was followed in short order by two other trio albums (C3515 and C3523), both with the same personnel. Hailed as the “Arrival of the Year” by Metronome in the 1955 yearbook, Hawes was voted in 1956 “New Star” on piano by the annual Down Beat poll of leading jazz critics. In the same year (1956), after completing a highly successful engagement at The Tiffany in L.A., he left for an extended cross country tour which kept him on the move for six months. In the course of this tour, he met many Eastern jazzmen and was most impressed by Thelonious Monk as a musician and personality. In 1957 he made another tour back East, and enjoyed playing with Oscar Pettiford and Paul Chambers.

Although his first three albums for Contemporary were with his own trio, Hawes enjoys working with a quartet. “You can do more rhythmic things and you can have more beats going. The full rhythm of drums, bass and guitar gives you two instruments to play melody (guitar and piano) and two instruments to play rhythm (drums and bass) and keep the beat going. Then you can switch around. I like to hear other people play solos because it’s inspiring, and gives you ideas other than your own to conjure with.”

—–

Liner Notes by Arnold Shaw

Volume Two

Comparatively little has been written on the art of jazz improvisation. How the jazzman plays notes, devises figures, invents rhythm, concocts chords which were not in his mind a moment before he plays them; how he succeeds in spontaneously altering the notes, chords, figures and rhythm patterns so as to achieve freshness and a jazz feeling — these are the enigmas of the creative process.

Of his approach to improvisation, here is what Hawes has revealingly said: “You know the tune you’re going to play and after you play the melody through, it comes time for you to blow. You build your solo on the chords as they go by and you use the chord changes to tell your story… Just like, maybe a painter painting a picture, he has his brushes. Well, his brushes are the chord changes. What he paints is what he’s thinking about, so what kind of solo you play is what comes out of your mind, or the soul that you have for that song you’re playing. I believe that the way a person thinks usually comes out in his playing. You’ve got to really feel what you’re doing. Even the way my hands feel on the keys, that has a lot to do with what I play. I like my hands to feel good when they’re playing. Like between the black notes and the white notes on the piano, when I’m phrasing I like to have my hands fall off right so I can feel like I’m getting into it. If I know that my hands are feeling good, then I know that I’m phrasing right. If something feels awkward — well, I’m doing something wrong. I don’t try to play too much at first. I like to start out just playing a few things and then keep building, chorus by chorus, until you reach a big climax, when you’re playing to your fullest capabilities, in other words, where you’re really doing everything you can do — then after that you cool it and give yourself a little rest and you’re playing just a few things while you’re thinking about something else to play… Sometimes I think about the melody. But before I think about the melody, I think about the ‘underneath notes’ of the melody — the harmony notes that move under the top notes and show where the chord goes…”

Three concepts stand out in Hawes’ statement. While they involve technical matters, their import may be grasped by the layman without resorting to technical exposition. The three concepts pivot on the words: climax, chord changes, and “underneath notes.” Climax in improvisation is not different from climax in a story so that it is not too difficult to discern. Hawes’ procedure in adding notes, chords and figures, chorus after chorus, may be studied in Do Nothin’ Till You Hear From Me or Will You Still Be Mine where the third choruses are like the full, complex, colorful flowers that have sprouted from the small, simple buds of the original melody. The building process involves a variation of chord changes and, in turn, of the “underneath notes,” which significantly determine the sequence of chords.

Imitation is an important device for developing a piece of music and, of course, as an improvisational technique. It involves the repetition of a line or riff in another key, a different register, or on another instrument. As an instance of imitation, listen to the way guitarist Hall picks up and echoes Hawes’ melodic line in Will You Still Be Mine and Hampton’s Pulpit. In the latter, consider also the question and answer interplay between piano and bass, another device for variation. More important than either of these improvisational procedures is the shifting of accents and the variation of rhythm figures, which are wonderfully displayed in Hawes’ improvised solos on April in Paris, Woody’n You and Blue ‘N Boogie. Used imaginatively and with feeling, and not just manipulated mentally, these devices produce constantly fresh variants of well-known melodies.

How an improviser handles these devices depends on a number of factors: specifically, on whether he is interested in a) motion or placidity, b) dissonance or prettiness, c) a thick sound or a delicate texture, d) static or shifting rhythm patterns, e) short or long melodic lines. To understand Hawes’ handling of these factors, it will be helpful to see him in relation to other contemporary jazz pianists.

At the moment, there are three axes in jazz piano. I prefer the word ‘axis’ to school or style because within any one so-called school, there are sufficient tensions to make for a direction rather than a pat definition. For example, Brubeck and Tristano have more in common as representatives of a modernist-classical-intellectual-far-out approach than Brubeck and Garner.

Yet there are also obvious contrasts and conflicts. Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell as practitioners of bop piano share more characteristics than do Powell and Oscar Peterson. Yet there is an undeniable gulf between Monk’s emphasis on an economy of notes as against Powell’s tendency toward flooding and constant motion. Here then are the three major current axes in contemporary jazz piano: 1) a Garner-Tatum axis, stressing rich harmonies and the fullness and pumping beat of stride piano; 2) a Brubeck-Tristano axis, combining modern classical polyrhythms and poly-harmonies with jazz improvisation; and 3) a Bud Powell-Thelonious Monk axis, stressing a single note, horizontal style, using the left hand for punctuation, and playing off the beat.

Clearly, Hampton Hawes is closest to the bop axis of Powell and Monk. He strives for constant motion rather than placidity, tart rather than pretty harmonies, a delicate rather than a thick density, shifting rhythm patterns, and longer rather than shorter lines.

Within the bop axis, the main influence on Hawes’ improvising comes from an alto sax player rather than any pianist. In 1947 when Hawes was just turning nineteen, one of the founders of bop, the late, great Charlie Parker came out to Hampton’s native Los Angeles. Hawes not only met and listened to Bird, which proved a turning point in many a contemporary musician’s career, but he played with him for almost two months in Howard McGhee‘s band. Not too long ago, Hawes described Parker’s influence as having to do “with Bird’s conception of time.” Working with Parker, Hawes began taking liberties with time, “playing double time or letting a couple of beats go by to make the beat stand out – not just playing on top of it all the time.” Hawes emphasizes: “I think Parker has influenced me more than anybody, even piano players.”

The Parker bop influence is apparent in All Night Session! in many ways, not the least significant being Hawes’ choice of material. Included among the sixteen selections are four Gillespie compositions that have become bop classics – Groovin’ High, Woody’n You, Two Bass Hit and Blue ‘N Boogie. Comparison of Hawes’ version of Woody’n You with the Modern Jazz Quartet‘s chamber music treatment of the same reveals a style in which there is greater dissonance, more pronounced changes of rhythm figures, swifter shifting of accents and a feeling of intensity that reminds one of Parker. Characteristic of these selections, and particularly of an original composition Takin’ Care, is Parker’s device of altering melodic passages containing few notes with figures full of gusts of fast-moving notes.

—–

Liner Notes by Arnold Shaw

Volume Three

In All Night Session! the characteristic sound of the quartet is produced by the interplay between Hawes and Red Mitchell’s bass. As with many West Coast combos, Hawes prefers a drummer with a light beat. In selection after selection, the rhythmic pulse is generated by the bass while the drums are heard only in the delicate ching of an afterbeat cymbal.

Bassist Red Mitchell, a native New Yorker (born September 20, 1927) is, like many West Coasters, a Californian by migration. He has been steadily associated on records with Hampton Hawes from the first Hawes Trio album made in June 1955. Mitchell has also recorded with combos led by Barney Kessel, Tal Farlow, Red Norvo, Jack Montrose, and Gerry Mulligan. He has also made two LP’s with combos of his own, the most recent Presenting Red Mitchell for Contemporary (C3538).

Although Red played piano with Chubby Jackson (at the Royal Roost in 1949), and alto sax in an Army band, he had a new love the moment he traded 15 cartons of cigarettes for a string bass while in Germany. Up until then he had been studying the piano on his own. He cultivated the bass in the same way, acquiring bass methods by Bob Haggart and Simandl, and industriously plowing his way through them. Mitchell also learned by listening to every bass player who came his way, on records or live, acquiring in the process an unusual knowledge of the entire range of bassists.

“I guess the first bass player that really thrilled me,” Red recently stated, “was Walter Page.” This was on a Count Basie record even before Mitchell had settled on the bass as his instrument. Ray Brown, who played with Dizzy Gillespie, “just turned me inside out. I heard the new music, the new phrasing.” At Minton’s, Red heard Charlie Mingus, who “frightened me… because I remember the way he went up to the top of the fiddle.” But the greatest of all bass players to Red was the late Jimmy Blanton, who is generally credited with inaugurating the revolution that took the bass out of the rhythm section in the late 30’s and made a melody instrument of it.

Despite his talking intimacy with the top bassmen of our time, Red feels that he has been more influenced by horn men and pianists than by bassists. He mentions among the jazzmen he has admired and studied: saxists Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, Lester Young, Al Cohn, Zoot Sims, and Jimmy Giuffre; trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis; and pianists John Lewis and Hampton Hawes.

As an improviser, Red is to be heard to advantage particularly in Broadway and Groovin’ High, both of which reveal not only a prodigious command of technique but fast, jazz solos of the very highest order. Red has a fat tone when occasion demands and there are slow, singing solos to be heard in Hampton’s Pulpit and The Devil and the Deep Blue Sea. Insofar as giving the Hawes piano the rhythmic support it needs, Red’s pulsating beat is masterful.

In the fall of 1956 Jim Hall, then a member of Chico Hamilton‘s group, used to sit in for kicks when Hawes’ Trio worked at the Tiffany in Los Angeles. The discovered kinship of feeling between the two led to the invitation that made Hall a part of All Night Session!. Born in Buffalo, New York on December 4, 1930, Hall was raised in the Buckeye State. Although he attended the well-known Cleveland Institute of Music, receiving a Bachelor’s degree in music, Jim studied guitar privately with Brenton Banks. His style was also formed by constant listening to recordings of the abortive American genius Charlie Christian and the French gypsy giant of the guitar, Django Reinhardt, Other formative influences include the tenor sax playing of Bill Perkins and Zoot Sims, whose modern improvisational lines are to be heard in Hall’s solos.

At the precocious age of 13, Jim Hall began working with local Ohio bands. For short or long periods, he was associated with the Bob Hardaway Quartet, Ken Hanna‘s band, with whom he made a Capitol album, and later, with the Dave Pell Octet. In the early months of 1955, Hall came to Los Angeles and began studying with the classical guitarist Vincente Gomez. At about the same time, drummer Chico Hamilton hired Jim for his newly formed Quintet.

It was the Hamilton Quintet that brought Hall’s name into the national jazz arena. During the latter part of ’55 and early ’56, Jim toured with Chico’s Quintet, recorded three albums for Pacific Jazz with it, and appeared in a film Cool and Groovy. The Hamilton association also led to Hall’s recording for Pacific Jazz with a trio of his own that included the late Carl Perkins on piano and Red Mitchell, on bass. Since making All Night Session! with Hawes, Hall has been steadily associated with the trio of Jimmy Giuffre. He also is to be heard with John Lewis in a new album just made by Lewis without the Modern Jazz Quartet.

Of the role of the drums in his Quartet, Hampton Hawes has said: “I don’t like a drummer that plays a heavy foot pedal because it has the dull sound of somebody trudging down a street. I like the drums to sound like a heartbeat – just like a heartbeat pumping blood into the tune, nice and smooth… I don’t like a heavy-footed drummer.”

In drummer Bruz Freeman, born in Chicago on August 11, 1921 and a West Coaster since 1954, Hawes found an ideal man for his quartet. Bruz became interested in music through his two brothers, tenorman Von and guitarist George. At 9 he was playing violin. At 13 he shifted to the piano. Then came the drums. After a stint in the Air Force, during which he flew with Percy Heath of the Modern Jazz Quartet (Percy as a fighter and Bruz as a bomber pilot), he returned to Chicago to gig with a group known as the Freeman Brothers Band. Later he played at Chicago’s Beehive, silting in with men like Sonny Stitt, Bird, and J. J. Johnson. Before he settled in California, he played for singers Ella Fitzgerald and Lurlean Hunter and went on the road with Anita O’Day and Sarah Vaughan. “On drums,” he says, “Max [Roach] is my man. On other instruments: Miles Davis, J. J. and Bird.”

Of the All Night Session!, Hawes recently said reflectively: “It’s hard to put into words how good it feels to play jazz when it’s really swinging. That’s the greatest feeling I’ve ever had in my life. I’ve reached a point where the music fills you up so much emotionally that you feel like shouting hallelujah – like people do in church when they’re converted to God. That’s the way I was feeling the night we recorded All Night Session.”