Rec. Date : April 5, 1957

Stream this Album

Vibes : Milt Jackson

Bass : Percy Heath

Drums : Connie Kay

Piano : John Lewis

Billboard : 07/22/1957

Spotlight on… selection

Another excellent jazz package from Atlantic, “a characteristic 40-minute set” by MJQ that allows for more solo improvisation than do previous sets for label. Performance of diverse program reaffirms group’s rare integration and facility to delineate feelings from one end of the emotional scale to the other. Vibist Milt Jackson, especially, is in fine form here. Dealer should have no trouble selling this set.

Album Cover of the Week

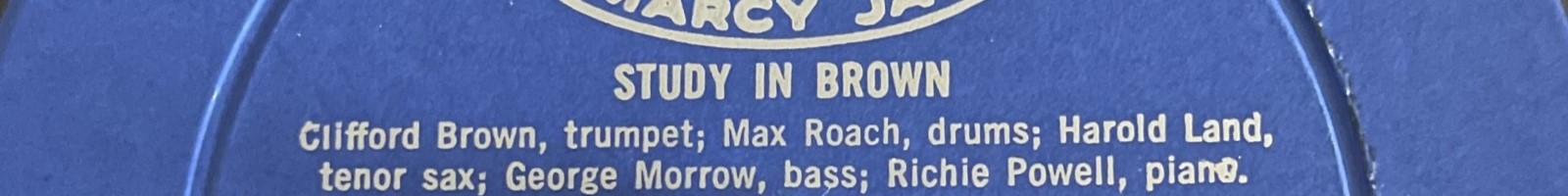

This very interesting setting by noted portrait photographer, Fabian Bachrach, has already been the subject of much discussion. There is no copy on the cover – just the solemn, stiff group pose. Clever, off-beat idea is a choice display piece and is sure to attract attention.

—–

Cashbox : 07/27/1957

The outfit is an excellent disk seller, and from the remarkably expression sessions to be found here, no wonder! These are seven bands, including one five song medley, that display a basic swing approach intricately furnished with brilliant solo, and combined performances. Vibist Milt Jackson is one of the mainstays of the takes. Outstanding jazz artistry.

—–

Army Times

Tom Scanlan : 08/10/1957

The Modern Jazz Quartet is the finest combo in jazz today, according to many jazz critics. I certainly do not agree but I suspect that the unit’s newest LP will be praised highly by most jazz writers and will interest a good many readers of this column.

The album is one of the group’s “characteristic sets,” according to John Lewis, musical director and pianist of the quartet, and the selections are ones that the quartet has played often.

There is a ballad medley (tempo: slow, almost dreary); Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea (featuring excellent vibes by Milt Jackson, the swinger of the group and therefore as vital to the MJQ as Desmond is to Brubeck, it seems to me.); La Ronde, mostly a drum solo (brushes) by Connie Kay and like most drum solos dull; Night in Tunisia; Yesterdays; Bags’ Groove (the blues); and Baden-Baden.

The minority view here is that this is pleasant, team, pretty, chamber music, not exciting jazz. And, for me, Lewis remains an extremely limited pianist for one who receives such high praise (you’ll find typical one-handed or one-fingered solos by Lewis on Ghost of a Chance, Devil, and Bags’ Groove). To this Johnny-Out-of-Step reviewer, Milt Jackson creates what excitement is to be found in the MJQ’s music. (Jackson, incidentally, is the beardless one on the cover.)

However, many find this group’s music continually stimulating and those who do will surely want this LP. Liner notes, by Nat Hentoff, are well worth reading.

—–

Arlington Heights Herald

Paul Little : 07/25/1957

Atlantic Records of New York City, headed by Nesuhi Ertegun who used to direct Good Time Jazz so ably, are taking the spotlight with some excellent 12-inch progressive jazz platters.

One of these, The Modern Jazz Quartet, has just been released, and we think you’ll enjoy it. The combo features John Lewis at the piano, Percy Heath on vibraphone, Milt Jackson on bass and Connie Kay on drums. Using a chamber style for compactness, Lewis has nonetheless managed to produce fascinatingly complex tonalities and rhythms. His medley which includes Body and Soul, My Old Flame, and I Don’t Stand the Ghost of a Chance with You, is typical of his flair for inventive arranging. And his original La Ronde, which gives Connie Kay some magnificent solo drum opportunities, is worth the price of the platter.

—–

Cincinnati Post

Dale Stevens : 08/31/1957

What lies ahead for jazz?

The last really important era in jazz was bop, in the days immediately following World War II when Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie emerged as the new giants. Since that time almost all the alto men has sounded just like Bird; the trumpeters like Diz or his cooler counterpart, Miles Davis.

Of the important new groups and individuals, none has as yet signaled a genuine new path for jazz. Dave Brubeck has been interesting, but apparently is not influencing others to follow his path. Ditto Gerry Mulligan.

Closest to an influence is the Modern Jazz Quartet, whose soft subtle lines can appeal to the most commercial-minded music fan, yet delight the serious jazz follower by their constant interplay and new forms. Using piano-vibes-bass-drum, the MJQ commands an uncommonly wide range of ideas from a chamber music approach to the simple old blues. It’s the combination of those two feelings that makes the Modern Jazz Quartet unique.

The blues get them across to the pop audience; the chamber-music effect, combined with the swinging rhythm of jazz, connects them with both the longhair and jazz fan.

The link between jazz and classics has been forecast for several years. And you find many present-day musicians who are heading that way – Jimmy Giuffre, Teddy Charles, Johnny Richards, John Lewis of the MJQ, George Russell, Charlie Mingus.

But, although a few are forging the difficult path ahead, most of the modernists have slipped backward into a sort of melodic bop. That’s especially true of the jazz units bordering on commercialism, such as J.J. Johnson and Kai Winding.

Bop still is the basic, though it’s been mellowed with a touch of the blues. Though it’s more lyrical in 1957 than it was in 1947, it still deals in long, complex ensemble phrases that have replaced the swing era’s riffs; the many-noted solos that require greater mastery of the instrument; the involved, advanced harmony that again requires deeper knowledge of music.

The major difference between the old bop and the new is that in 1947, Parker and Gillespie delighted in complex phrases to cover up the fact they were borrowing All The Things You Are or How High the Moon. Today, writers such as Quincy Jones and Gigi Gryce and George Russell are writing melodic originals and to that degree, drifting with the Modern Jazz Quartet and the others towards a more classical jazz, i.e. written jazz.

To prove this theory, listen to these recent albums which are among the finder modern jazz albums of the present season:

The Modern Jazz Quartet. I can honestly say that I have never introduced a friend to jazz who wasn’t especially impressed with the MJQ. Forty minutes of pretty, driving jazz, from Body and Soul to Night in Tunisia to Baden-Baden.

—–

Miami Herald

Fred Sherman : 08/11/1957

MJQ are the magic letters of the modern jazz world. They stand for Modern Jazz Quartet. You’ll find the group’s portrait on a new album that has no name. Nothing on the cover but the faces of the four men who have done so much to chamberize sounds that had their beginning in the gin mills of New Orleans.

This latest is a brilliant performance by leader John Lewis, Milt Jackson, Connie Kay and Percy Heath; certainly the best thing the group has done since the Concorde album on the Prestige label. Lewis takes a stronger role for his piano. And I feel Lewis is one of the top three pianists in jazz today. Listen to him on Ghost of a Chance in the opening medley and with the Kay drumming on Bags’ Groove.

Don’t miss this one.

—–

Musical Courier

Deanne Arkus : August, 1957

As the sound of the Debussy harp trio echoed into silence, its performers yielded the Town Hall stage to another chamber ensemble. Again an impressionist mood was created with soft, iridescent tones, lush harmonies, and melodies that moved with easy grace through canons and triple fugues. The scene was a “Music for Moderns” concert held in New York last May, and this ensemble was the Modern Jazz Quartet.

The program presented jazz and classical music side by side and showed them to be happily coexistent and compatible. Since jazz has come only recently into the country’s concert halls, many people were realizing for the first time that jazz is a serious art form. For most “classical” musicians, the concert was a revelation. The reviews pronounced it as an artistic success. Said Jay Harrison, chief critic of the N.Y. Herald Tribune: “The Modern Jazz Quartet is quite a wondrous group. The ensemble plays in a jazz style that is the very opposite of hectic or frantic. Perhaps the style might be called ‘cool’; others may prefer the erudite. But to these ears it was svelte, the artists together producing sounds not only fascinating but genuinely musical. And since the quartet seems to breathe as one even in matters of rubato the performance was stimulating in a refreshingly artistic sense. In sum, the Modern Jazz mean are a credit to the calling, an asset to the field of Jazz.”

Jazz has come a long way from its bawdy beginnings in New Orleans’ infamous Storyville. Through the efforts of dedicated and ingenious musicians, it has followed an evolutionary path to what is known today as “modern” jazz. As its name implies, the Modern Jazz Quartet epitomizes this style and stands in the foreground. Over the past year it has won every leading jazz poll (the International Critics’, Down Beat, Metronome, etc.) and its heavily booked season of world-wide concert tours and night club dates confirms a rapidly growing popularity in all music circles.

Each member of the quartet is a major artist in his own right. Composer-pianist John Lewis, a graduate (B.A., M.A.) of the Manhattan School of Music and the Dizzy Gillespie Band, has played with and arranged music for the leading jazzmen of the generation. In 1955, he and Gunther Schuller founded the Jazz and Classical Music Society for the purpose of presenting performances of rarely heard modern works. In addition to other projects, Mr. Lewis writes and arranges the music for the quartet.

Milt Jackson holds the position of eminence among vibraharpists, and Percy Heath is unsurpassed as a bass player. Both were former members of Dizzy Gillespie ensembles. Connie Kay, who was for some time drummer with “Pres” Lester Young, is also one of the foremost virtuosos of his instrument.

Typical of an increasing number of jazz artists today, these men are all well-schooled musicians. They combine the art of improvisation with a secure knowledge of harmony and form. Counterpoint, in the shape of a canon of fugue, is used consistently, and spontaneity and freedom are always evident. The exponents of “modern” jazz find a creative challenge in the development of musical form.

But we wondered, “Does this trend toward extended form, toward subdued and refined sound, mean that jazz is trading in its vestments for the cloak of classical music?” We decided to ask John Lewis, leader of MJQ. Mr. Lewis, a handsome young man whose manner bespeaks the quiet intensity of his music, had apparently come across this question before. His answer was a soft spoken, but definite, “No! Classical music and jazz stand individually as art forms,” he explained, “and one cannot take the place of the other. We are dealing with two completely different concepts of music training – the European and the American. Classical musicians, even here in the United States, are trained in the European tradition. They are taught to interpret the works of composers by reading notes. The ideal is to reproduce, as closely as possible, the composer’s original intention. On the other hand, the essence of jazz is improvisation. There may be a certain plan of harmony or form, but the actual composing is done by the performer.”

Mr. Lewis believes that classical musicians and jazz musicians can learn a great deal from one another. “Jazz has always been basically polyphonic,” he revealed, “but through study of Baroque forms, we have learned to refine this polyphony. We also agree with the composers of the classical period who found that the small chamber ensemble provides the most sensitive means of communication, and we’ve turned away from larger groups and deemphasized solo playing At the same time, classical composers from Stravinsky to Bernstein have assimilated in their styles the rhythms and harmonies of the jazz idiom. Also, classical performers might find it helpful to develop the freedom and confidence that come with a knowledge of improvisation.” MJQ is planning an unusual experiment along these lines. They plan to appear as soloists with civic orchestras throughout the nation in “concerto grosso” style. The scores will leave room for improvisation in all of the parts.

The widespread interest in jazz has now permeated the educational system. Schools and colleges have incorporated into their music curricula credited courses in jazz and improvisation. Starting August 12, MJQ itself will act as quartet-in-residence at the first session of the School of Jazz at Music Barn in Lenox, MA. The school, of which John Lewis is executive director, is an outgrowth of Music Inn’s “Folk and Jazz Roundtables.” In September the quartet will make a cross-country tour with “Jazz at the Philharmonic” and on October 19 they will leave for a five-month tour throughout Europe.

It is not difficult to understand why a program of classic and jazz proved so entirely successful at Town Hall. Though the two forms have grown in separate ways, there are many parallels. Most important of all, they both produce serious musicians – and the primary interest of a serious musician is the future and development of good music.

—–

Pittsburgh Courier

Harold L. Keith : 08/10/1957

Atlantic records, whose packaging has been of a tremendous variety of late, presents the MJQ in what is undisputedly its best thus far. Not only is it the best, but leader John Lewis concurs.

The album is a fitting send-off for the group, which will play on the European circuit this fall.

Standards to be enjoyed include A Night in Tunisia, They Say It’s Wonderful, Body and Soul, My Old Flame and I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance With You.

—–

Playboy Magazine : October, 1957

The pomp and pretension that have marked so much of the Modern Jazz Quartet‘s work are pleasantly and conspicuously absent from their latest effort. This time the cats are content just to swing most of the time, reminding us that three-quarters of the group are Gillespie alumni. Night in Tunisia and Bags’ Groove are top drawer. There’s even a medley of five ballads, mostly media for Milt Jackson‘s melodic vibrations. And lamp that cover pic: the four solemn poseurs constitute the most unintentionally funny pic of the year.

—–

San Bernardino County Sun

Jim Angelo : 07/28/1957

Album of the week: The Modern Jazz Quartet. Amid a plethora of quartets – vocal as well as instrumental – The Modern Jazz Quartet is a group with complete musical integrity – brilliant conception, flawless balance, tasteful execution.

Hear, for instance, their sensitive, delicate medley of My Old Flame and Body and Soul, their imaginative Yesterdays, as well as their vital, pulsing Night in Tunisia and Baden-Baden. Nothing blatant or garish here, just delightful, listenable music.

Some critics have wasted much effort trying to prove that the MJQ’s work is not jazz. Other dissertations have been written which claim the reverse. Best thing to do is not worry about it. Just listen. It’s great!

—–

Saturday Review

Martin Williams : 09/14/1957

This disc is devoted largely to solos (with a minimum of scoring) on pieces which the group has had in its repertory for some time. If the group could not bring this off, its neo-classicisms would mean nothing; because it can (and usually does), they do mean something. In his efforts to play gently, J. Lewis seems to be backing away from the keyboard, and there are again hints that the group may be losing a unified swing that has mad its past work so fine. The polyphony of Lewis and Jackson continues to be a delight.

—–

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Charles Menees : 08/11/1957

The Modern Jazz Quartet gets away from fugal and other extended forms to concentrate principally on standard tunes and swinging originals in its newest recording. Actually the Atlantic 12-inch LP is titleless, with nothing but a fine color photograph of the quartet on the jacket cover. Those who have accused the MJQ of playing nothing but cold intellectual music will have to keep quiet about this collection, for here is a performance with consistent emotional appeal. Some complexity, yes, but orderliness and controlled excitement. Such oldies as Yesterdays, My Old Flame and Body and Soul keep their original ballidie flavor, but with undeniable jam feeling underneath. John Lewis, pianist and leader of the ensemble, for La Ronde, which features the drumming of Connie Kay. Milt Jackson, the vibraharpist in the group, is composer of Bags’ Groove (“Bags is Jackson’s nickname) and co-writer of Baden-Baden, which has become the quartet’s closing theme at the end of each set when playing in public. Another welcome offering is Dizzy Gillespie‘s Night in Tunisia.

—–

Washington Post

Paul Sampson : 08/04/1957

In spite of sporadic comebacks by big bands, most of the best jazz today is played by small combos. They range from superbly organized groups like the Modern Jazz Quartet to congeries gathered to make a recording.

I’ll start this survey of recent combo records with the new LP by my favorite group, The Modern Jazz Quartet. John Lewis, pianist and musical director of the quartet, a man not given to overstatement, says this is its best LP. Although I have been enthusiastic about past MJQ records and like certain pieces on them better than some on this one, I agree that none of the past LPs have been so consistently superb as this one. There’s not a dull moment or a wasted note.

To those who say the MJQ doesn’t have deep roots in jazz, the lusty Night in Tunisia, rocking, blues-rich Bags Groove and fleet Baden-Baden are the obvious answers. It doesn’t take deep listening, however, to hear the basic jazz feeling in the medium tempo Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea; or in Milt Jackson‘s feathery solo on Yesterdays or in all of Lewis’ precise, beautifully organized and swinging solos.

Couple with this jazz feeling is a remarkable rapport that informs the ensembles with structural strength and gives soloists just the right backgrounds. This is one of the few groups that will repay close listening with new pleasures at every hearing.

—–

Down Beat : 08/22/1957

Don Gold : 4.5 stars

The latest in Atlantic’s MJQ series represents a typical 40-minute set by that group. Although the group has moments of an embalmed nature, it is an erudite, consistent, ambitious and able collection of jazzmen. This assortment illustrates the MJQ at its best.

Each member of the group makes a contribution to the end of making the quartet swing in its own sweet way. Jackson is at ease on ballads and up-tempo races. Lewis‘ spare but meaningful piano complements Jackson’s pulsating expression. Heath and Kay provide superb rhythmic support, with Kay particularly coming into his own as a subtle, intelligent drummer.

The ballad medley contains five standards, including They Say It’s Wonderful, How Deep is the Ocean, and My Old Flame. All are performed impeccably. Devil is a cleverly conceived tour de force. Jackson spurs the group through the wondrously alive Tunisia. The set ends, as it does in person, with a vigorously played closing theme, Baden-Baden.

This is well-tempered jazz, produced by minds more than familiar with the intricacies of modern jazz and the complexities of classical tradition. Frankly, there are moments when I would prefer that the group add a permanent horn, to vary the tone colors created and enhance the harmonic potential of the group. However fascinating the group as is, I feel that another vibrant voice could give it more potency. Nevertheless, in most ways, and certainly in terms of the jazz recorded today, this is pertinent music.

—–

Liner Notes by Nat Hentoff

John Lewis, musical director of The Modern Jazz Quartet, is an enemy of complacency. He and his colleagues rehearse at least two or three times a week when they are not chained to a schedule of one-nighters. During a three week stay at Music Inn in the Berkshires in the summer of 1956, the MJQ rehearsed daily – the lure of the lake and other sun-lit diversions notwithstanding.

The reason for this continual honing of their material and themselves by the MJQ is that John is a musical director who knows exactly what he wants, and will not rest content until he and the group fulfill the potential of any given piece.

A corollary of this attitude is John’s disinclination to express more than guarded satisfaction with most of what the unit has done on recordings. When, therefore, he said with his customary gentle firmness that this album is the best the MJQ has done musically, I was curious to discover why he felt able to make what is for him so lightning-bolt a declaration.

“I like the album” he began, “because the selections are old in our repertoire so that we’ve played them a great deal. They’re old enough for us to see if we can play, if we can really get out of them and out of ourselves what is there to be gotten. After hearing the album, I feel we can play.”

“This album,” John continued, “is one of our characteristic 40-minute sets. That’s a long time to play and sustain interest and strength. I feel we did here. And the rhythm holds up all the way, another reason I like the set. The numbers also sound the way they actually do sound when we are at our best in a club or at a concert. Again, we’ve played them so long that we know how we want them to sound.”

It will be noted that there is a considerable amount of solo playing in the set. “We had to pay for that, to be able to do that,” John explained. “They went for themselves, but that was possible because the quartet before had done so many pieces under direction. They knew what to do and I knew what to do when going for ourselves.”

There are several ballads in this collection, and John has pointed to a note on the ballad in jazz by John Wilson (Ballads & Blues/Milt Jackson, Atlantic 1242) as most clearly expressing his own ideas on the subject. “It is the ballad,” Wilson wrote, “as most of us have learned, that separates the jazz improvisor from the jazz drudge. It is possible to swing a ballad forcibly enough to invest it with an appearance of jazz feeling, but in the process much of its balladry is dissipated. Or, if the inherent prettiness in a ballad is too carefully retained, the effect may be more funereal than jazzlike.” Wilson went on to indicate that Milt’s task on that album was “to keep the ballads balladic but to play them as jazz.” He succeeded, and so does the MJQ as a unit.

In pointing out that the members of the quartet “go for themselves” more than before in this album, John did not mean to indicate that improvisation is a minor aspect of their other work. “The most important thing we’re doing,” he emphasized, “the bulk of what we play is improvisation. The rest is to give us a framework. And even those frames get moved or bent to fit what we’re trying to project. A frame may last for a while, and if it wears out, it has to be changed too. Anything wears out in time, and changes. All of what we do is relative, and can be different at different minutes in different sets in different nights.”

The essential importance of each individual in the MJQ is clear in John’s discussion of how he writes for the group. “I have to listen and listen to Milt and Percy and Connie to absorb as much of them as I can so that I can write things that will be natural to them, that will be as close to their musical personalities as I can get. And that way too I can make it possible for them to best express themselves musically in what I write and for me to express myself.”

Milt begins the ballad medley, recalling a visual-analytical description of his approach by André Hodeir in the April, 1956, Jazz-Hot: “Once he has chosen his theme, he respects its contours, an attitude which facilitates a generally happy choice of melodies by him. Knowing the quality of his sonority, he loves to let the long notes reverberate – reverberate purely – and even elongate them, it seems, to give them an increase of plasticity as Miles Davis does with obviously different means but an analogous intention. There’s the impression that Milt is listening to himself play with an ear that is not at all complacent but that is, in a certain sense, charmed; and that he leaves certain sounds (whose resonance has not been entirely extinguished) only with regret and only under the imperative necessity of the melodic chain.”

Much has been written about Milt and his assured position as the most creative modern jazz vibist. The two qualities, in addition to his conception, that particularly individuate and fire his work and his “soul” (his ability to communicate open emotion directly); and his beat which is in itself an instantly clear definition of what it is to swing.

The style of John Lewis as a soloist, as player of complementary lines to another protagonist, and in straight comping is most accurately described, I feel, as “classic” in the denotative sense of that term. I cite Webster’s New International Dictionary (Unabridged): “Of or pertaining to a system regarded as embodying authoritative principles and methods; in accordance with a coherent system considered as having its parts perfectly coordinated with their purpose…”

In all of John’s work, written and pianistic, there is a clear depth of feeling for tradition, for the roots of the jazz language. In almost anything he plays, for example, one can hear the mark of the blues in John.

Percy Heath has matured with constantly growing strength in the past three years. His tone has become fuller and firmer, his conception more consistent. He is in temperament and determination an exciting group player, and is willing to learn and grow as an individual through the learning and growth of the group. When I interviewed the then MJQ for a March, 1955 High Fidelity story, Percy said: “The music we’re playing has become part of me, and it’s such a challenge to try to say well what this music has to say that it’ll be extremely gratifying if I’m ever able to fully accomplish that – to interpret our music fully.” Percy has come a very long way in that time, and he was eloquent then.

Connie Kay may well be the most underestimated member of the MJQ. This is partly due to the subtle usages of percussion in the MJQ’s work and partly to Connie’s own quietly observant, humorously reserved mien. He’s a drummer of rare consistency of taste and with the further capacity to meet the extraordinary dynamics-demands of the unit. There are passages in some works like John Lewis’ Variation No. 1 On “God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen” (in Atlantic 1247 The Modern Jazz Quartet At Music Inn), in which Connie has to provide the kind of shading within shading that would have ben the perfect accompaniment for the limitless numbers of angels who used to have to dance on that one medieval polemical pin. Withal, Connie swings – he pulsates with flowing surety – in whatever he does and through whatever manner of percussion instrument he strokes, attacks or otherwise animates. It is instructive to compare his version of the drum section of La Ronde Suite with previous interpretations by Kenny Clarke. I do not compare them qualitatively, because I feel each is meaningful in his own voice; but the comparison indicates how much room for individuality is left for the individual members of the MJQ.

Of the rest of the music, there is little to say that the music does not itself make clear. I would note that the album contains two examples of jazz standards that have grown from within jazz, thereby adding to the body of relatively indigenous jazz material from from Oh Didn’t He Ramble to In A Mellotone to Godchild. The two here are Dizzy Gillespie‘s Night In Tunisia, and Milt Jackson’s talk on and in the marrow of the blues, Bag’s Groove, “Bags” being Milt Jackson’s nom-de-jazz-guerre.

Another point to be made about this album is that although it does not contain any of the quartet’s longer works like Fontessa, it does set the problem again of where music like the MJQ’s can find an optimum place to be played. Even though there is more “going for oneself” in the LP, this is still music of unusual subtlety that requires an attentive audience, an audience sufficiently interested in listening to become active listeners. The most rewarding listening, after all, is that in which the hearer participates in the music, giving of himself emotionally and intellectually as he receives.

On this subject, John Lewis has remarked: “People who play should think more about where they’re playing. When you’re playing in one kind of place, you have to do things that fit that place. Now, if you’re in clubs, and feels better off in concerts, you should work in that direction as much as you can. There should be – but doesn’t yet exist – something in between clubs and concerts, a place to play that isn’t as formal as a concert, not so cold (relatively speaking) but also where the bottles and glasses aren’t tinkling either.”

“The quartet, for example, does much better in places where people can listen attentively. This is possible in some clubs, but not all. Musicians, to repeat, should start thinking in terms of what kind of settings they’re best in. Some big bands might feel better in a theatre than a concert hall, because what they do, if well produced, can be turned into good theatre. Lionel Hampton, for one, shouldn’t play concert halls; he’d probably, however, make exciting theatre. And then there are some people who are not theatrical at all, and wouldn’t fit at all in theatres.”

John has obviously thought considerably about where the MJQ can best be heard and can best hear itself. Although the MJQ continues to play clubs, an increasing number of its dates are at colleges and concerts. In the fall of 1957, they began a European tour that will set a valuable precedent for groups of their kind. Instead of touring for a short, intensive period as part of a “package” with other groups, the MJQ is going for itself. It participates first in the Donaueschingen Festival of Contemporary Music in Germany, October 19-25. The quartet then plays six weeks in Germany, Austria and Switzerland in college towns and small halls in large cities. Four more weeks in France and Belgium are to follow plus possible dates in Scandinavia and an initial tour of Britain in January of February. In time, the MJQ may be the first modern jazz unit to create a continuing international circuit of which haste, night club and “packages” will be subsidiary and diminishing parts.

The final Milt Jackson and Ray Brown track, the quartet’s closing theme for the end of each set, is Baden-Baden. The Modern Jazz Quartet’s selection of European place names for some of its titles (Concorde, Versailles) is a glancing indication, among other larger ones in his conversation, that John is perhaps the fullest example yet of international jazz musician whose jazz roots are in America but whose tastes, curiosities and life-experiences are not restricted to any one milieu.

Jazz has obviously become an international language, and I expect that in the decades ahead, more and more of its practitioners will also become internationalized.

It would not be the first time jazzmen have set an example in the breaking of artificial barriers.