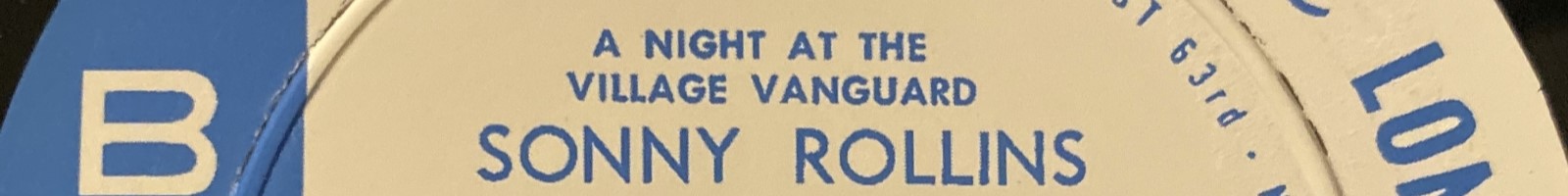

Prestige – PRLP 7038

Rec. Date : March 22, 1956

Tenor Sax : Sonny Rollins

Bass : George Morrow

Drums : Max Roach

Piano : Richie Powell

Trumpet : Clifford Brown

Listening to Prestige : #167

Stream this Album

Billboard : 08/25/1956

Score of 80

Altho Rollins gets top billing here (for contractual reasons) this is the same combo that cut the most recent, excellent Max Roach–Clifford Brown disk on EmArcy. The modern jazz performances here are at least as rewarding, but the billing should favor the EmArcy set. Rollins, A Parker-influenced tenorman, is picking up steam and should develop into a market entity. The late Brown is superb. A big market is obvious for this one, if dealers push it.

—–

High Fidelity : September 1956

The warmth and mutually responsive qualities of this group (once led by Max Roach and the late Clifford Brown) are more apparent on this disk than on any other issued under the Brown-Roach name. The addition of Sonny Rollins is a great help, for he is a saxophonist with a big, rich tone like those of Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster, but without their sentimentality. The ballad Count Your Blessings, for instance, manages to be expressive without losing the lithe strength that is Rollins’ most effective quality. The group also produces a happy tour de force on Valse Hot, a really good jazz waltz garnished with relaxed solos by Rollins, Brown, and Richie Powell. Powell, who was killed in the same automobile crash that took Brown’s like a few months ago, plays with casual charm throughout the disk.

—–

Miami Herald

Fred Sherman : 08/19/1956

Two Albums Are Memorial to Young Trumpeter

Modern jazz was dealt a setback two months ago when young trumpeter Clifford Brown was killed in an auto accident while on the way to a night club engagement in Chicago. He had just done a date in his hometown of Wilmington, and it had been sort of a celebration of the local boy makes good type.

Also killed in the highway crash were pianist Richie Powell (Bud‘s young brother) and his wife.

It was is if Brown was destined to find his death on the highway. In 1950, also in June, he was injured seriously and spent almost a year in a hospital. He was just 20 then. Three years later he was hailed by jazz critics as the new star of the trumpet. But now it is all over except for the records. And this week we have two albums. One is EmArcy’s called Clifford Brown and Max Roach at Basin Street. The other is Prestige’s Sonny Rollins Plus Four.

It is the same quintet on both albums. With Brown are drummer Roach, tenor saxophonist Rollins, bassist George Morrow and pianist Powell.

The album covers were printed before Brown’s fatal accident. The EmArcy set, recorded Jan. 4 and Feb 16-17 is billed as providing “the most effective picture to date of the degree of integration, spirit and swing achieved by Brown and Roach and their worthy cohorts.” In a supplement mailed to critics, EmArcy says this is “an album which may well be considered a memorial” to Brown and then adds that “it will someday be considered a collector’s item since it is the last LP ever to be released by the great combination of Brown and Roach.”

That made me curious about the Prestige product. The recording date isn’t given, so I got in touch with prexy Bob Weinstock. He said his album was recorded March 22 at Van Gelder’s studios in Hackensack, NJ.

I am betting three to one that it won’t be long before somebody is out with a Clifford Brown album that sells the “memorial” angle heavy on the album cover.

When that happens, I ask you to keep these two fine albums in mind. They are new and fresh, not something dredged up from the tape cans.

For review purposes, I think it best to separate them.

Prestige Preferred

The Prestige product is preferred in this corner because the two horns are picked up more cleanly. In Valse Hot, Brown has a solo that is a real tingler. You can almost see him stepping up to the mic for his bit. I had the feeling he had stepped right into the room.

And I had the same sensation with some shining work by Rollins on Kiss and Run. I head it on equipment with a woofer and a tweeter.

High point in the album is the dueling by Rollins and Brown on Pent-Up House, a Powell original. This track is tremendous.

Honors Shared

EmArcy’s album is more of a team victory with drummer Max Roaching emerging the strong man of the session. He lays the groundwork for a frantic kind of jazz with a stunning beat.

For those of you who think of the drum as an oom-pah-pah instrument, I urge you to listen to Roach work on this album. Particularly his finesse on Time, a Powell original.

Rollins is exciting on I’ll Remember April, chasing with Brown through all the melodic possibilities of the ballads.

And the three ballads on the opening side serve as an overture before the quintet breaks out with a bit called Powell’s Prances with the trumpet and drum driving hard.

This is good jazz.

(We will be hearing more quintet music from Roach because he is taking over as head man. The new group will include pianist Barry Harris and trumpeter Donald Byrd in addition to Rollins and Morrow.)

—–

Oakland Tribune

Russ Wilson : 10/28/1956

Sonny Rollins Plus 4 is one of the last recordings by the quintet before the summer auto crash which claimed the lives of trumpeter Clifford Brown and pianist Richie Powell. The other members of the group, in addition to tenorist Rollins, were drummer Max Roach and bassist George Morrow. The album, besides being a fine example of imaginative, driving modern jazz, demonstrates the kinship which had developed in the combo and which carried with it the promise of even greater attainments. Brown is brilliant and Rollins plays with a warmth not heretofore evident and which bodes well for the future.

—–

San Francisco Chronicle

Ralph J. Gleason : 09/30/1956

Clifford Brown is on this album, one of the last dates he made before his death. Rollins is the leader of the hard-swinging, no romanticism and no nonsense school of New York jazzmen and although I find a little of him goes a long way, this is one of his better efforts.

—–

San Francisco Examiner

C.H. Garrigues : 10/14/1956

Sonny Rollins Plus 4 demonstrates something of what happened to the tenor since [the Hawkins days. Rollins is featured; his is supposed to be the lead horn. And yet, what you hear is, chiefly, the fine trumpet of the late, great Clifford Brown. And this, not essentially because of any lack on Rollins’ part, but because styles have changed: against the cool, liquid trumpet which Brown blue, a true tenor style would have shown harshly discordant.

—–

Saturday Review

Wilder Hobson : 10/27/1956

Very much inside jazz, and robustly so, is a modern quartet with Sonny Rollins tenor sax; the late Clifford Brown and the late Richie Powell, trumpet and piano; Max Roach, drums; and George Morrow, bass. These are all members of the varsity- – lusty, adventuresome, experienced – and they do particularly well by a jazz waltz, Valse Hot (whose basic theme, however, is something of a bore) and an easy-riding effort, Pent-Up House, which completely belies the neurotic suggestion of its title. Those who wonder how a waltz can possibly come under the jazz category will find their answer here. To state the matter no doubt oversimply, it is a question of applying the instinct for momentum in suspended rhythm to 3/4 rather than 4/4 time. I see no reason why players of this talent should not apply themselves to the themes of Johann Strauss with equally persuasive effort. But I am bound to admit that I like the sophisticated Sonny Rollins quintet when they are looking back to the barrel house rather more than when they are gazing toward the distant palaces of the Hapsburgs.

—–

Down Beat : 10/17/1956

Nat Hentoff : 4.5 stars

Sonny Rollins Plus 4 is the Max Roach–Clifford Brown quintet before the bitter accident. George Morrow is on bass, and the late Richie Powell on piano. Sonny wrote the captivatingly-realized jazz waltz and also the last track, which is, I think, the most image-evoking title of the year. At the time of the crash, the quintet had begun to reach a rare fused unity that came from playing long hours together and, basically, from a warm similarity in musical viewpoint. The newest member, Rollins, had apparently become comfortable and relaxed in the combo.

Powell had improved very much, as is tragically evident here and on the Basin Street EmArcy LP. He was playing with much more confidence, drive, and imagination.

Brownie was moving inexorably toward status as one of the very greatest of jazz hornmen, turning more and more of his irrepressible exuberance in the joy of playing and in having such command of his horn into consistently explosive flying, rising lines that were less and less deflected by flurries of somewhat gratuitous notes, although the dizzying speed and fluency remained.

Morrow had grown considerably and Max continued to be a source of power and stimulation, searching out fresh, challenging broken-rhythm patters while driving the band.

All this actuality and promise of the quintet is here, with Rollins playing the most sustainedly creative tenor I’ve heard on record by him before. His impressive rhythmic strength is there as always, but the conception has broadened and relaxed and there is less of the inflexible hardness that had marred some previous performances. The record is very much recommended.

—–

Liner Notes by Ira Gitler

Slowly but surely, Sonny Rollins has started to get some of the recognition due to him. His recordings, his appearances as a member of the Max Roach–Clifford Brown group and, perhaps most importantly, the growing list of tenormen he is influencing, have all contributed to this new found esteem.

Musicians have recognized Sonny as the important new reed voice; one who not only can swing but can also get inside of the chords and “stretch out” on them.

When I read critics delivering praise to the young tenormen who, although they swing, never really get their teeth into more than a few chords in a row and invariably skim along the surface choosing the dullest portion of the chord, I scratch my head in wonder. The main irritant to me is not the opposition to Sonny or the praise of lesser musicians but the lack of understanding of the whole school of tenor playing. When there were only the Hawkins, Young, Berry and Evans influences to ascertain, the critics’ task was simpler. Today’s tenormen have been filtered through so many influences that sometimes their various styles seem to elude the critics’ “hearing.” It must have been Bird who confused them. They may acknowledge him because they would appear ridiculous if they didn’t, but they couldn’t have had any real feeling for his music if they didn’t appreciate Sonny. This is not to say that Sonny has reached Bird’s pinnacle but he has gotten Bird’s message and captured the spirit of his music. But back to critics. One of them has labeled Sonny’s style “hard bop” a not entirely inaccurate, but too convenient labeling which suffers not so much from this labeling but from the manner said critic dumps anyone who plays even a Stittian, much less Rollins-like, phrase into this large cubbyhole he has built with his do-it-yourself kit.

In the table below I have attempted to illuminate the styles of some of the contemporary tenormen of this school; ones who are affiliated with it directly and others who are peripheral. A detailed explanation might entail a chapter in a book and I don’t have the space, but there are interesting observations to be made. For instance, Dexter Gordon, who was one of John Coltrane‘s first influences when Gordon was playing in the Forties, is now influenced by the same men who has been a more recent factor in Coltrane’s playing, Sonny Rollins.

I also would have liked to bring in more of Pres’ disciples (Sims, Cohn) and their little brothers (Perkins, Kamuca) but again space prevents me.

Through the courtesy of EmArcy, Clifford Brown and Max Roach appear here with Sonny and the two other regular members of Brown-Roach Inc., Richie Powell and George George Morrow, are on hand too.

Valse Hot, Sonny composition, is the first successful jazz waltz since Thelonious Monk interpreted Carolina Moon. Max, incidentally, was also the drummer on that one. There is an introductory interlude before the main melody and this is restated before each solo. Sonny and Brownie swing tenderly around the floor in turn, Richie has the third and Max fills out everyone’s dance card with his solo.

Sam Coslow, who gave us My Old Flame, among other fine songs penned Kiss And Run. There’s more “running” than kissing in Sonny’s version. He and Brownie are fleet but not fleeting. These two musicians are perfect examples of how vital the Park-Gillespie tradition is when played at its best. Richie Powell shows brother Bud’s influence but remains his own man. After his solo, Sonny, Max and Brownie converse for a chorus and then Sonny and Brownie make it a two way talk for one more.

Everyone keeps coming on and on in I Feel A Song Coming On. Max, who shows how to swing a soloist and never be monotonous, keeps things moving at a fantastic clip as the soloists cruise and cook at top speed.

Sonny delivers Count Your Blessings as a medium bounce rather than as a ballad with the help of an interlude by Richie Powell.

The most engaging, Rollins original, Pent-Up House has Brownie and Sonny playing pat-a-cake with the lead figures of the melody line. Brownie, who is in warm form throughout the entire proceedings, comes in with George Morrow and Max strolling behind him for two choruses before Richie joins him with his comping. Sonny picks up Brownie’s tag line and strolls some himself in the same manner. Both hornmen are searching and heartfelt soloists in what is the high point of the set to me. After Richie finds a vein of Silver, Max mines a Roach gem and leads into the final statement.